The Intro

It’s one of pop’s sadder ironies that it took the shocking murder of John Lennon to give him his first solo number 1, with a song that begins ‘Our life together is so precious together’. The former Beatle had returned to music in 1980, and was talking about his hope for the new decade in his final interviews. The year instead ended with vigils across the globe for a murdered hero.

Before

‘Let’s take a chance and fly away, somewhere.’

Lennon was born 40 years previous, on 9 October 1940, at Liverpool Maternity Hospital. His childhood was famously a mix tragedy and luck. His father Alfred, a n’e’er-do-well merchant seaman, was away from home at the time. At four, his mother, Julia, gave her sister Mimi custody. Aged six, Lennon’s father visited and attempted to take his estranged son to live in New Zealand with him, but it didn’t happen and there would be no further contact between the two until Beatlemania.

Raised by the well-to-do Mimi and her husband, Lennon was considered the class clown, and would draw surreal cartoons for his school magazine The Daily Howl. He was regularly visited by Julia, who bought him his first guitar in 1956. Famously, his aunt turned her nose up at this, saying: ‘The guitar’s all very well, John, but you’ll never make a living out of it.’ The 15-year-old Lennon payed no mind to this and started a band – The Quarrymen. In 1957, at a legendary village fete in Woolton, Lennon met Paul McCartney and asked him to join the band.

Lennon’s mother was killed when she was hit by a car driven by an off-duty policeman who was under the influence. The trauma brought Lennon and McCartney, who had lost his own mother to cancer, closer together, but the already wayward Lennon drowned his sorrows and frequently got into fights. Now a Teddy Boy, he was accepted into the Liverpool College of Art.

Despite McCartney’s father’s disapproval, Lennon and McCartney began writing songs together. Despite initial reluctance, Lennon agreed to allow George Harrison into the band. The three guitarists’ ranks were soon bolstered by Lennon’s art school friend Stuart Sutcliffe on bass, even though he could hardly play. By 1960, they were The Beatles, and Lennon was their leader. They went to Hamburg for a residency, along with new drummer Pete Best. Three residences in and The Beatles, buoyed by the drug Preludin and playing stupidly long sets, became a force to be reckoned with.

Brian Epstein became their manager in 1962, and although the rebellious Lennon bristled at the idea of cleaning up their act and donning suits, he relented. When Sutcliffe decided tasty in Hamburg, McCartney took over on bass, and Best was replaced by Ringo Starr before their debut single on Parlophone, Love Me Do.

From The Beatles rise to fame, through to Beatlemania and the British Invasion, Lennon was their acerbic leader. Brilliantly witty, sarcastic, and prone to many unfortunate ‘cripple’ impressions, he and McCartney were the greatest songwriting team of all time. Writing most of their early work together, they co-wrote three number 1 singles in 1963 – From Me to You, She Loves You (the greatest 60s chart-topper) and I Want to Hold Your Hand.

In 1964 The Beatles released their first film – A Hard Day’s Night. Lennon wrote the film and accompanying LP’s title track, and also the 1964 Christmas number 1, I Feel Fine, which featured feedback from Lennon in the intro. The Beatles had begun to widen their sonic palette.

By 1965, despite being at the peak of their commercial fame, Lennon was feeling disillusioned. He was overweight, exhausted by Beatlemania and literally crying out for help, which translated into the title track of their second film – not that their screaming fans were noticing – they were too busy shaking their heads to yet another pop classic. He and Harrison took LSD for the first time, and further experimentation came from one of their greatest mid-period songs, Ticket to Ride – another primarily Lennon song, and another number 1. But in a sign that Lennon and McCartney were growing apart as songwriting partners, they disagreed on their Christmas single, resulting in the former’s Day Tripper sharing equal billing with We Can Work It Out – although Lennon came up with the pleading middle eight of McCartney’s track.

1966 was a tumultuous year for the Fab Four. An interview with Lennon about the decreasing popularity of the church was blown out of all proportion, resulting in a rare public apology, most likely forced on him by Epstein. Nevertheless, records were burned, and Lennon was threatened. All this, plus the group exhaustion with their endless touring, resulting in a decision that would ultimately change popular music. They didn’t go public with the decision, but that August, they stopped performing for audiences. Despite all this, they entered their imperial phase of studio recording. Lennon was integral in this, contributing the concept of backwards recording in Rain and then the amazing experimentation of Tomorrow Never Knows.

The increasingly pioneering sounds coming out of Abbey Road contributed to the cultural zeitgeist of the Summer of Love in 1967. Although perhaps their single finest record – Lennon’s Strawberry Fields Forever, combined with Penny Lane – failed to top the charts, they were at the peak of their creative powers, releasing Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. And Lennon was responsible for the anthemic number 1 All You Need Is Love, too. But Lennon was lost in constant use of LSD, and later said it came close to erasing his identity. This and the loss of Epstein resulted in McCartney increasingly looking like the band’s new leader, and this started to cause problems.

Lennon’s wife Cynthia found her husband at home with the artist Yoko Ono in May 1968, after they had recorded what became the experimental LP Two Virgins. Soon, the duo were inseparable, for most of the rest of his life. This inevitably had an impact on the already often strained relationships of The Beatles, who wrote and recorded much of their eponymous double album as solo songs, which the rest of the band would merely provide backing to. Although Lennon and Ono were turned on to heroin, his decreasing use of LSD saw a return to his more fiery personality. While more experimental than ever on the sound collage of Revolution 9 and the unreleased What’s the New Mary Jane?, Lennon’s pop dominance of the band had decreased so much, he only contributed one song to the two number 1 singles in 1968, and Revolution was relegated to the B-side of Hey Jude – written by McCartney to give comfort to Lennon’s son, Julian, while his parents divorced.

While Peter Jackson’s Get Back has proved that the Let It Be sessions of early 1969 weren’t as miserable as the world was led to believe, the initial sessions were an often bleak affair, yet by the time of their last public appearance on the rooftop of Apple Studios, Lennon was in his element, offering surreal banter inbetween their set, which featured one of his best later-Beatles-period songs, Don’t Let Me Down.

Relieved that the project was over, The Beatles splintered. Relations between the four were not fab, as Lennon persuaded Harrison and Starr to sign Allen Klein as their new manager, while McCartney relented. Lennon focused on Ono, developing their new project, the Plastic Ono Band. Most of the duo’s material between 1969 and 1974 was credited to this revolving line-up, featuring, at various points, Harrison, Starr, Eric Clapton, Klaus Voorman and Keith Moon. Lennon and Ono married that March, resulting in the last Beatles number 1 in the band’s lifetime – The Ballad of John and Yoko. The first Plastic Ono Band release was the anti-war classic Give Peace a Chance, in July, which peaked at two. The band went on a brief hiatus while The Beatles recorded what was to be their swansong. Lennon was absent for some of the sessions after a car accident with Ono, but his raunchy Come Together was promoted to an A-side.

With Abbey Road in the can, Lennon went back to concentrating on his new band, and privately decided he was going to leave The Beatles. The grim account of heroin withdrawal, Cold Turkey, followed, then the concert recording Live Peace in Toronto 1969 was released as the 60s – and unbeknownst to the world – The Beatles, drew to a close. The dream was over.

The 70s got off to a great start for Lennon, releasing perhaps his greatest post-Beatles single, Instant Karma!, which began a long working relationship with the unhinged Phil Spector. McCartney angered Lennon, by announcing he had left The Beatles, as publicity for his first solo album. Lennon had been working through primal therapy, resulting in the raw, often painfully honest eponymous album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, one of the last lyrics of which was ‘Don’t believe in Beatles’.

In 1971, Lennon and McCartney were publicly fighting via song, resulting in the bitter How Do You Sleep? on Lennon’s best solo LP, Imagine. That August he and Ono moved to live in New York and began their association with radical left-wing politics. President Richard Nixon’s administration became determined to deport him. At Christmas the couple released their festive classic Happy Xmas (War Is Over) with the Harlem Community Choir.

Over the next few years, Lennon’s commercial standing began to drop, with he and Ono releasing the highly political but average Some Time in New York City with Elephant’s Memory in 1972. Then aLennon self-produced and released the decidedly poor Mind Games in late-1973 – although the title track is excellent. He and Ono’s marital problems resulted in their separation, and the start of an 18-month period immortalised as the ‘Lost Weekend’, in which he had a relationship with his and Ono’s personal assistant, May Pang. Lennon ran wild, often with Harry Nilsson, drinking heavily and making headlines.

During that time he released Walls and Bridges, featuring one of his best solo songs, #9 Dream. Elton John featured on Whatever Gets You thru the Night – his first US number 1. Lennon had made a bet that that if the single topped the charts, he’d perform live with John, which he duly did. Lennon and Ono were reunited in 1975, and he co-wrote and performed on David Bowie’s first US number 1, Fame. But following Rock ‘n’ Roll, a covers album, in 1975, Lennon went on hiatus to help raise his and Ono’s son, Sean, and would only record the occasional demo when inspiration took hold.

When McCartney released the single Coming Up in 1980, Lennon was impressed and even said so publicly, with the former Beatles having made amends and occasionally meeting during the 70s. Then in June, Lennon was involved in a sailing trip which was hit by a storm. As all the crew fell ill, Lennon was forced to take control, and the incident affected him profoundly. His confidence restored, and with a newfound zest for life, he decided to release a new album with his wife – their first since Some Time in New York City.

Ono approached producer Jack Douglas with a batch of demos, and that August they started recording in secret at New York City’s Hit Factory, as Lennon was concerned the sessions might not be good enough. By September they were more confident and went public that they were back. The newly formed Geffen Records was successful, thanks in part to David Geffen making it clear he regarded Ono’s contributions as the same quality as Lennon’s.

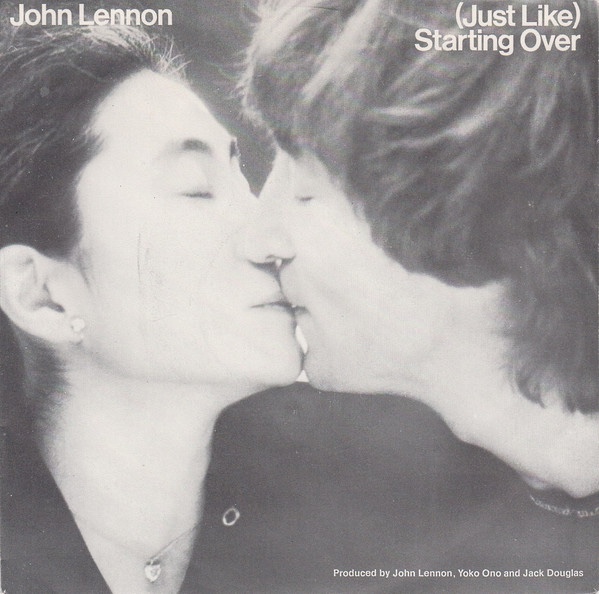

With its warm, nostalgic 50s feel and lyrics about rejuvenation, it made perfect sense to place (Just Like) Starting Over at the start of Double Fantasy, and to make it his comeback single. The song’s origins began with the demo recordings Don’t Be Crazy and My Life. Lennon wrote Starting Over, as it was originally called, in Bermuda, and despite being recorded on 9 August, it was one of the last songs to be completed for the album, mixed at the Record Plant on 25 and 26 September. Featuring on the recording are David Bowie’s guitarist Earl Slick, Hugh McCracken, also on guitar, King Crimson’s Tony Levin on bass, keyboardist George Small, Sly and the Family Stone drummer Andy Newmark and Arthur Jenkins on percussion. Providing the doo-wop-style backing vocals are Michelle Simpson, Cassandra Wooten, Cheryl Manson Jacks and Eric Troyer.

Review

(Just Like) Starting Over (the extra bit in brackets was added to avoid confusion with Dolly Parton’s Starting Over Again) begins with a deliberate callback to Mother, the opening track on John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band 10 years previous. Whereas the bells that toll on Mother are slow and foreboding, and reminiscent of a funeral bell, the ringing here is light and airy, and (sadly ironically) herald a hopeful, optimistic Lennon, softened by years of time as a father and absent from the music business. His fire seems to be gone, he’s retreated into the rock’n’roll of his youth, and he’s perfectly content with that. And so am I.

Lennon might not have thought (Just Like) Starting Over was the best track on Double Fantasy, but it’s one of the strongest on what is otherwise a pretty average album. Had he not been out of the public eye for so long, this track wouldn’t have had that added poignancy, and wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Rock ‘n’ Roll, that ropey collection of mostly poor covers that soundtracked his youth. Gone is one of the best voices of his generation, as Lennon ramps the pastiche levels up even more by singing in a style that brings to mind Elvis Presley and Roy Orbison. Sure, this idealistic vision of Lennon and Ono is schmaltzy, saccharine and most likely somewhat false, but it’s rather charming and lovely. And of course, in hindsight, those lyrics are desperately sad. Thumbs down to the awfully mixed backing vocals, though. Was it a failed attempt by Douglas to capture that echoey 50s sound?

After

(Just Like) Starting Over was released in the UK on 23 October, and a day later in the US. Riding on a wave of goodwill as the world welcomed back an old friend, the single was Lennon’s strongest performing record in the UK since Happy Xmas (War Is Over), which had reached four in 1971. It peaked at eight, and although reviews for Double Fantasy were warning that Lennon had lost his bite (and he was looking older than his years and was painfully thin), the future looked bright. He and Ono had recorded enough material for a follow-up, and with his confidence returning, maybe we’d see some of that fire return. Of course, we’ll never know.

Lennon’s comeback single had slipped to 21 here, and six in the US by 8 December, but promotional work continued for Double Fantasy, released a few weeks prior. At around 5pm, he was stopped outside his home, the Dakota building, by a random fan. Lennon was photographed signing a copy of his new album for the grinning Mark Chapman, and then left with Ono for a session at the Record Plant. At approximately 10.50pm Lennon and Ono returned and were walking through the archway of the Dakota, when Chapman shot him twice in the back and twice more in the shoulder at close range. Lennon was pronounced dead less than half an hour later.

Shocked, confused and in mourning, the world chose to pay tribute to Lennon, who had soundtracked the lives of so many, by listening to his music. In much the same way his hero Buddy Holly’s It Doesn’t Matter Anymore became a posthumous chart-topper after his untimely death, (Just Like) Starting Over inevitably began to sell once more. 12 days after his death, Lennon had his first solo number 1. Such was the magnitude of his loss, it wouldn’t be his last.

The Outro

In 2010 Ono and Douglas released Double Fantasy Stripped Down, which was an attempt to wipe away the studio sheen of the original album. The version of (Just Like) Starting Over is thankfully free of those odd backing vocals, and is OK but pretty inconsequential.

The Info

Written by

John Lennon

Producers

John Lennon, Yoko Ono & Jack Douglas

Weeks at number 1

1 (20-26 December)

Trivia

Births

20 December: Footballer Ashley Cole/Footballer Fitz Hall

21 December: Scottish actress Louise Linton

Deaths

20 December: Locomotive engineer Roland Bond/Footballer Tom Waring

22 December: Magician Lewis Ganson/Physician Thomas Cecil Hunt

23 December: Playwright Frank Norman/Anglican bishop Ambrose Reeves

25 December: Comedian Fred Emney/Explorer Quintin Riley